Jim Dandys Stock and Poultry Feed 218

Hercules Posey: George Washington's unsung enslaved chef

(Image credit:

Peter Horree/Alamy

)

In the late 18th Century, Philadelphia was a city of high-end cuisine; however, few know that many of its culinary masters were of African descent like Hercules Posey.

E

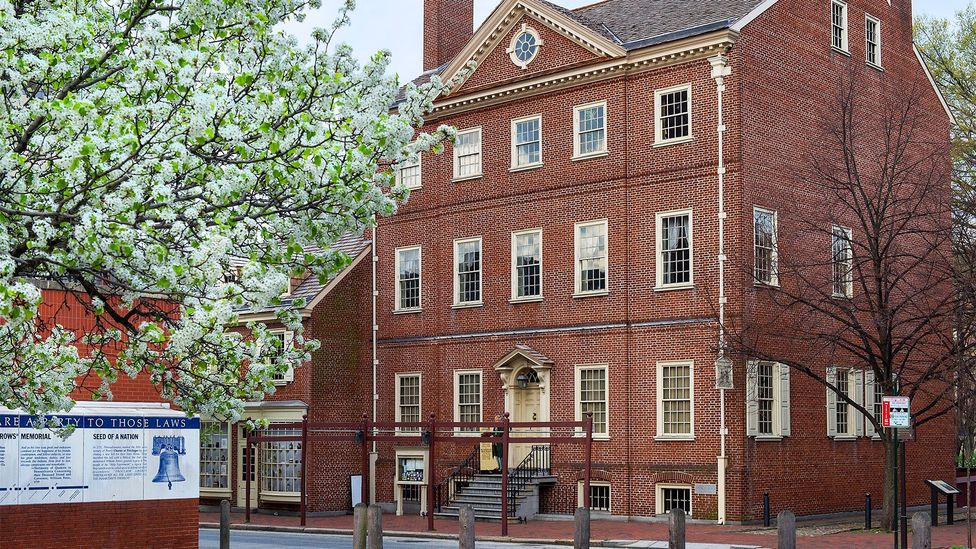

Each year, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, sees millions of heritage-seeking tourists who traipse the reconstructed brick pathways of the old city, eager to see the sites that birthed ideas of American liberty such as Independence Hall, where the Declaration of Independence was signed in 1776, and the iconic Liberty Bell. But like its ties to democracy, Philadelphia's connection to great American food culture has roots that reach into the distant past, roots that until recently have been obscured in the history books.

Much of the fledgeling nation's culinary excellence was achieved in the homes of its Founding Fathers like George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, where high-end cuisine was perfected not by white cooks but by enslaved chefs of African descent. These highly skilled chefs were influenced by the city's bountiful European, Caribbean and Native American exchange of culinary ideas and techniques, as well as their own heritage.

According to Dr Kelley Fanto Deetz, author of Bound to the Fire: How Virginia's Enslaved Cooks Helped Invent American Cuisine, a mix of West African, European, Native American foodways collided in the colonies, by force," she said, "and this collision found a world stage in places like Washington's dining room table in Philadelphia."

Preparing the food that made its way to Washington's tables was the unsung haute culinarian Hercules Posey. Posey was unique among his peers in that he was famous in his own time and was acknowledged by white society. He had a larger than life persona, and, as head chef, a position of power in the household, as well as some quasi-freedoms like the ability to leave the house on his own when he was not working and to earn money selling leftovers from the kitchen.

Hercules Posey would have been familiar with Philadelphia's City Tavern in his time (Credit: John Greim/Getty Images)

I spent a dozen years researching on Posey for my novel The General's Cook, piecing together the details of his remarkable life through painstaking research of Washington's household accounts, letters to and from his Philadelphia steward and personal secretary, census documents and other ephemera. Unlike the lives of their white contemporaries, the life events of enslaved people are not well recorded in the public record, appearing only as property footnotes in the files of their enslavers, making reconstruction of their lives incredibly difficult.

Hercules Posey's Philadelphia

The vestiges of Hercules Posey's life in Philadelphia remain tantalisingly within reach for visitors who know where to look.

Steps away from the Liberty Bell, tourists can visit the President's House, where Posey lived and worked. The open-air site is interpreted through the lives of those George Washington enslaved there.

Cross the street to visit the Declaration (Graff) House where Posey's contemporary Chef James Hemmings lived with his enslaver Thomas Jefferson during his time in Philadelphia.

In the Germantown section of the city, the Deshler-Morris house, also known as the Germantown White House, was where George Washington spent the summer of 1794 to avoid the yellow fever epidemic raging in the city. Posey cooked in this kitchen.

City Tavern and Man Full of Trouble tavern (now a private home) on Spruce Street are places with which Posey would have been familiar in his time.

The Reading Terminal Market offers the energy and flavour of the open-air markets of Posey's day, featuring goods from around the region and world.

Because Posey was notable in his own time, there are more records of his life than of others like him – although this information is still incredibly sparse. However, Washington's step grandson, George Washington Parke Custis, chose to immortalise the chef in an biographical sketch in his book Reflections and Private Memoirs of Washington. Much what we know about Posey's towering persona is gleaned in Custis' single description. Recalling his childhood in the presidential mansion, he wrote about Posey as "a culinary artiste" and "dandy", with "great muscular power" and a "master spirit", whose "underlings flew to his command" (among those underlings were paid white servants).

Posey was possibly a teenager when he came to Mount Vernon, Washington's estate in Virginia, about 150 miles south-west of Philadelphia. He apprenticed there under the enslaved cooks Doll and Nathan, who managed the kitchen for many decades, and he mastered his craft so well that Washington brought him to cook at the President's House in Philadelphia in 1790. It was here in Philadelphia that Posey was exposed to and inspired by ingredients and cooking techniques from throughout the nation – and the world.

In the time the chef resided in Philadelphia, the city was positioned ideally in the middle of the nation, and thanks to the wide, navigable Susquehanna, Delaware and Schuylkill rivers, regionally produced vegetables, fruits, meats and dairy products like milk and butter arrived regularly at its open-air High Street Market. The rest of nation supplied what wasn't available locally. From the north came salted New England codfish and prized Connecticut onions along with upstate New York cheese. From the south there was Carolina rice and indigo, as well as tobacco from Virginia and Maryland.

You may also be interested in:

• How rice shaped the American South

• The chef preserving Gullah culture

• The Washington DC sauce drenched in debate

Furthermore, by the 1760s, Philadelphia's merchants had come to realise there was an untapped secondary market in the Caribbean (outside of the sugar, molasses and rum that went to ports like New York and Boston), and the city came to lead the nation in imports of ginger, allspice and black pepper, while controlling half of all coffee imports. Nutmeg, limes, pineapples, coconuts also made their way to Philadelphia as part of this robust West India Trade, and all were on offer in the city's ports for export, as well as its public markets and many taverns.

And, where the High Street Market sheds met the Delaware River, the harbour was jammed with trading ships loaded with olive oils from Spain; wines and oranges from Portugal, France and Germany; and tea from China – all part of the vast commercial network that made Philadelphia the busiest port on the American continent.

Hercules Posey cooked in the kitchen for George Washington's home at Mount Vernon (Credit: David Stuckel/Alamy)

"Philadelphia was the gateway to the Atlantic, a city that was central to the foundation of our nation and our understanding of what American food is," said Deetz, who is also the director of Collections and Visitor Engagement of Stratford Hall (the Virginia birthplace of confederate Civil War general Robert E Lee).

While none of Posey's recipes survived, period accounts detail meals with each course featuring a dizzying variety among dishes like roasted beef, veal, turkeys, ducks, fowls and ham as well as puddings, jellies, oranges, apples, nuts, figs and raisins. Depending on the season, there were oyster stews, other soups and pottages, as well as fruit pies, ice cream and seasonal fish. All were accompanied by various wines and were elegantly presented.

Understanding Posey lies in understanding his milieu. He moved to Philadelphia, a city that was a crossroads of culture, language, commerce and cuisine – much the way we think of New York City, London or Hong Kong today. Third and fourth generation European Americans with English or French ancestry – like George Washington – joined their Dutch- and Swedish-descent counterparts on the brick pavements of Philadelphia developed by William Penn on unceded indigenous Lenape land. In 1791, following the successful revolt of the enslaved on the Caribbean Island of St Domingue (now Haiti), French-speaking white refugees flooded the city, dragging their Creole-speaking enslaved in tow.

1770s Colonial-era American dish of baked stuffed striped bass garnished with lemon potato parsley (Credit: ClassicStock/Alamy)

These varied throngs gathered at Philadelphia's theatres, circuses and taverns, which according to Washington's household accounts, were also frequented by Posey. After his work was done, the presidential chef went out in the evening dressed to the nines with a gold pocket watch and gold headed cane, likely purchased with money he earned selling the usable scraps from Washington's kitchen that had value on the secondary market for uses like animal feed or fertiliser.

But while Posey experienced some autonomy, he wasn't free like his brethren in Philadelphia's Free Black community, which comprised nearly all of the 5% of the city's residents of African descent. Most had gained liberty thanks to Pennsylvania's 1780 Gradual Abolition Law that emancipated enslaved persons remaining in the Commonwealth for more than six months. However, Washington took great pains to subvert the Pennsylvania law and keep Posey and nine other enslaved Africans with him in Philadelphia in a condition of bondage. He did this by rotating Posey and the others out of the city into pro-slavery states like New Jersey across the Delaware River or back to Virginia, thereby continually resetting their time in the city.

Nonetheless, constant interactions with successful free food service workers, oystermen and farmers would have likely influenced Hercules' view of the world. He would have seen the path to another life – one in which his skill could sustain him if he were able to escape Washington's grasp.

According to Mount Vernon research historian Mary Thompson, the quasi liberty in which Posey lived – and his status in the kitchen – often confuses people into believing that he had an easier life than those who worked in the field.

A small dining room is set at George Washington's Mount Vernon Estate in Virginia (Credit: Joe Raedle/Getty Images)

"For some people, his 'status' might have made his story harder to understand. They think: why would he have wanted to leave, when he was working for one of the most important men of that time period and had the opportunity to be at, arguably, the summit of his profession as a cook?" said Thompson, who was among the few early scholars studying George Washington's enslaved people.

This confusion frustrates not only historians like Thompson but living history interpreters like Dontavius Williams who portrays Caesar, the highly skilled chef and master chocolatier enslaved at Stratford Hall in Virginia. In his interpretive work, Williams strives to make it clear that whatever limited autonomy or "pride of place" cooks like Posey were allowed, it did not make up for the fact that their labour and liberty were stolen.

"The work for all who were enslaved was gruelling in its own way. However, the work of the cook was extremely taxing mentally and emotionally. Working in extreme conditions under the scrutinising eye of his master and mistress, the enslaved cook had to perform at a high level at all times. There was no room for mistakes," said Williams. "Enslaved cooks had to hold it together and manage a staff while meeting the high standards of the family who owned them, and they worked even during those few times that other enslaved labourers didn't. It was literally a 24/7 job."

The importance of Philadelphia and its rich opportunities for free African Americans – and for cooks in particular – was becoming clear to Washington by the end of his time there. And so, after spending the summer of 1796 at Mt Vernon, he returned to Philadelphia leaving Posey behind believing he was planning to escape, thus cutting off his access to the city and its strong abolitionist network. But as George Washington Park Custis wrote, Posey was an extraordinary man, and on 22 February 1797, he walked away from Mount Vernon only to be seen once more, four years later in New York City.

The details of what happened after Posey's self-emancipation remained murky for 218 years until I and a research colleague of mine, Sara Krasne, found his gravesite, and we later discovered that he used the surname "Posey" (surnames were not common among enslaved people). He worked as a cook and caterer until his death on 15 May 1812. The discovery was the apex of all my years of research.

Colonial-style turkey pot pie at City Tavern restaurant in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (Credit: dbtravel/Alamy)

Although Posey spent nearly three times as long in New York as he did in Philadelphia, it is Philly where he made a name for himself. And his story is a testament to the standard for presidential dining, even now, but also to black contributions to American culinary history. As American chefs over the centuries sought to mimic what Posey created for the president's table, a style of haute American cuisine was born, one that highlighted local ingredients prepared in an elegant, though not lavish, style that was judiciously seasoned with the best additions the world market could offer.

"Chef Hercules is America's first celebrity chef, full stop," said Deetz. "His story of climbing the ranks in Washington's kitchen, to his flamboyant fashion style, rigid management style and his eventual escape from bondage, elevate his story to nothing short than legendary. He is an American hero."

Ramin Ganeshram is the author of The General's Cook a novel about the life of Hercules Posey. She is the Executive Director of the Westport Museum for History and Culture where, along with her colleague Sara Krasne, she was able to solve the 218 year old mystery of Chef Hercules Posey's life after self-emancipation from George Washington's Mount Vernon .

---

BBC.com's World's Table "smashes the kitchen ceiling" by changing the way the world thinks about food, through the past, present and future.

Join more than three million BBC Travel fans by liking us on Facebook , or follow us on Twitter and Instagram .

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter called "The Essential List". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

Source: https://www.bbc.com/travel/article/20220201-hercules-posey-george-washingtons-unsung-enslaved-chef

0 Response to "Jim Dandys Stock and Poultry Feed 218"

Post a Comment